|

|

|

|

|

|

Shinji Mine

(Nagoya University)

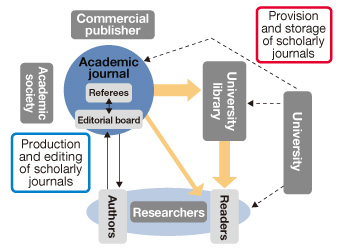

Figure 1: The publication and distribution process for scholarly journals

Source: Kurata Keiko(2007) Gakujutsu jōhō ryūtsū to ōpun akusesu (Scholarly communication and open access), Keiso Shobo, Tokyo, p. 71, figure 3, 5

The systems involved in scholarly communications are in the midst of far-reaching changes. In particular, the digitization of each part of the process, from the publication of journals to their access and storage, brings with it problems not envisioned in the era of print journals.

The publication and distribution process for scholarly journals outlined in Figure 1 has been transformed by digitization, largely in the form of e-journals. Journals are said to have four functions: the registration, archive, certification, and awareness of scholarly information (articles). The area most affected by digitization is the last of these, awareness or distribution of scholarly information; in particular, the movement to make it free of charge (open access) is gathering momentum and involving stakeholders around the world.

● Open Access

What is “open access”? While answers range from John Willinsky’s broad use of the term to encompass all practices, activities, and principles that increase access to the scholarly literature, to the more detailed definitions given in the widely recognized “BBB” (Budapest-Bethesda-Berlin) declarations, a fair amount of consensus does exist as to what open access is, at least in principle. In practice, however, depending on who grants the access, there is considerable divergence over what to make accessible, in what way, and to what extent. Willinsky groups these variations into ten “flavors” of open access, describing the economic model in each case and giving examples (see table). The situation at present is that stakeholders are trying out different kinds of open access, each choosing their own method.

In view of the scope of this newsletter, in the rest of this article I will focus on scholarly journals and discuss how university libraries view open access.

Table 1: Ten flavors of open access to journal articles

| |

Type of open access |

Economic models |

| 1 |

Home page |

University department maintains home pages for individual faculty members on which they place their papers and make them freely available. |

| 2 |

E-print archive |

An institution or academic subject area underwrites the hosting and maintenance of repository software, enabling members to self-archive published and unpublished materials. |

| 3 |

Author fee |

Author fees support immediate and complete access to open access journals (or, in some cases, to the individual articles for which fees were paid), with institutional and national memberships available to cover author fees. |

| 4 |

Subsidized |

Subsidy from scholarly society, institution and/or government/foundation enables immediate and complete access to open access journal. |

| 5 |

Dual-mode |

Subscriptions are collected for print edition and used to sustain both print edition and online open access edition. |

| 6 |

Delayed |

Subscription fees are collected for print edition and immediate access to online edition, with open access provided to content after a period of time (e.g., six to twelve months). |

| 7 |

Partial |

Open access is provided to a small selection of articles in each issue—serving as a marketing tool—whereas access to the rest of the issue requires subscription. |

| 8 |

Per capita |

Open access is offered to scholars and students in developing countries as a charitable contribution, with expense limited to registering institutions in an access management system. |

| 9 |

Indexing |

Open access to bibliographic information and abstracts is provided as a government service or, for publishers, a marketing tool, often with links to pay per view for the full text of articles. |

| 10 |

Cooperative |

Member institutions (e.g., libraries, scholarly associations) contribute to support of open access journals and development of publishing resources. |

Source: Willinsky, J (2006) The Access Principle: The Case for Open Access to Research and Scholarship, MIT Press, Cambridge, p.212–213 |

● University Libraries and Open Access

What, then, is the stance of university libraries? Considering the role they have played till now as an integral part of the academic information infrastructure, in principle they might be expected to support and promote open access (OA). The problem is, in effect, a practical one: how can they actually contribute to OA? In the days of print journals, it was the university library’s role to collect, store, and provide access to journals, but in the digital era provison and storage are taken care of directly by the publishers of e-journals; thus, before long, the main role of libraries in this regard will probably be collection (subscribing). Journal subscription prices have been soaring, and at this point it is unclear whether the upward trend will continue; under these conditions, will the role of the university library inevitably shrink?

Among the approaches to OA that university libraries are trying, one new idea is the institutional repository (IR). (This corresponds to “2. E-print archive” in the table.)

There are now over 1,400 institutional repositories worldwide and almost 120 in Japan alone; as of August 2009, they contained a total of over 20 million records. In Japan, in the last few years, the public has gained free access by this route to almost 700,000 documents that were low-priority for digitization or that had never been easy to obtain, such as papers in departmental bulletins, dissertation, and research reports. This, in itself, is a major achievement for the individual university libraries and research institutions that have created IRs. But even the libraries themselves do not seem to fully appreciate, in quantitative terms, the IRs’ overall contribution to the accessibility of journal articles, the key elements in scholarly communication.

IRs serve as repositories for a variety of scholarly information produced by individual universities. The materials collected, the parties with whom the libraries negotiate, the population served, and the storage method are all unlike those with which we have long been familiar in the handling of print journals and books. Thus, perhaps we should view IRs as unexplored territory, rather than a natural extension of the university library’s existing role. Therein lies the difficulty, for a university library, of creating and operating an IR.

For university libraries, the issues posed by OA, and especially by IRs, are far from easy. How will they cope with these challenges? Will they treat them as a golden opportunity to take on roles not previously performed by university libraries and develop and offer new and original scholarly communication services? Or will they adopt a “me-too” approach? The decisions involved should rest with the individual libraries, but those that choose the former path may well be taking on more than single institutions can handle, since IRs are a concept that has already outgrown the capacities of the university library.

Despite a number of recognized problems, the existing system for the publication and distribution of scholarly journals is not likely to change substantially in the next few years. The choices before us are not either-or, open-versus-paid as mutually exclusive ways of accessing journals. With the present arrangements as a basis, a variety of new approaches will probably continue to be tried for some time. The quest to maximize the value of scholarly information to the user should be a mutual concern for all stakeholders.

For university libraries that want to achieve open access through IRs, the outcome will likely hinge on their success in explaining their aims, in detail and at every stage, not only to other libraries but to researchers, academic societies, publishers, and university administrators, and thus in building partnerships and cooperative relations. |

|

|