Mitsuaki Nozaki

(High-Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK))

Source: Nozaki Mitsuaki (2012), 5th SPARC Japan Seminar 2012.

http://www.nii.ac.jp/sparc/event/2012/pdf/20121026_6.pdf

As the publication of academic papers moves increasingly toward digital and open access (OA) modes, this seems a good moment to return to first principles and think about what we expect from scholarly journals and libraries. I have served since about 2007 as contact person for my organization, the High-Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK), as it has faced decisions about its involvement in the Sponsoring Consortium for Open Access Publishing in Particle Physics (SCOAP3);1 concurrently, I have also played a part in the creation of the Physical Society of Japan’s OA journal Progress of Theoretical and Experimental Physics (PTEP).2 Although I am neither a librarian nor a publisher and can claim no expert knowledge in either area, these experiences have brought home to me the need for researchers to work together with those involved in libraries and publishing, and I hope this article will serve as a step in that direction.

I am writing this at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), where in the past two days I took part in the 6th Summit of Information Providers in Astronomy, Astrophysics and High-Energy Physics (AAHEP6).3 This summit, the first of the series I have attended, brought together over thirty people responsible for information access and management in the fields mentioned—from research institutes such as CERN, NASA, SLAC, and DESY, from organizations like arXiv.org and INSPIRE, and from publishers including APS, Elsevier, and IOP—for an exchange of views on topics ranging from journal publishing and archives to Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID), open data, and new evaluation standards to replace the impact factor. Thus, the meetings are a forum at which researchers, information storage and access specialists (perhaps the modern-day equivalent of librarians), and publishers try to solve their common problems.

The summit title refers to “information providers,” a perspective entirely absent in Japanese universities and research institutes. The job description covered by this term is far broader than the duties traditionally performed by libraries, yet it would be safe to say that, in Japan, researchers are not keen to take on such a role as it is not valued by the research community and, naturally enough, has no career path. Japanese have played almost no part in building and running the systems used on a daily basis by high-energy physicists, such as arXiv.org and INSPIRE (whose precursor was SLAC’s search and usage statistics system SPIRES). Japan’s researchers might indeed be said to be getting a free ride on systems created by their European and American colleagues, hoping for the most part just to pay the user fees as their sole contribution. A structure that would enable researchers and information specialists to collaborate in providing access to scholarly information is, I am afraid, lacking in this country.

Japanese research institutions simply cannot afford the personnel for such work, in contrast to their Western counterparts, which have invested the necessary resources in infrastructure. While recognizing this reality, in light of the importance of information-related work to the research infrastructure, one cannot help being struck by the flimsiness of the latter in Japan compared to the broad-based, historically rooted support for research in Western nations. For Japanese researchers and librarians, SCOAP3 may in fact be the first experience they have ever had of working together on a project. There is clearly a pressing need for a forum where researchers, who are both the source and the users of information, information management specialists such as librarians, and IT experts with the latest technology at their command can join in a three-way effort to study the optimal ways of managing information and making it available.

I digress, but to conclude these preliminary remarks: whether Japan will actively invest in such areas and add its voice to the international debate or merely continue to avail itself of world standards created by Western initiatives is a crucial question, one that I hope to see addressed urgently as an issue facing the nation (though it must also be discussed within each scientific field), perhaps with the National Institute of Informatics taking the lead. The challenge in the Internet era is to have Japan’s views reflected in international cooperation, rather than to try and build a system for Japan alone (unless we want another case of Galapagos syndrome).

Now to return to SCOAP3. In this article, I would like to consider OA journals as a whole by looking at this sponsoring consortium recently formed in the field of high-energy physics. To what extent it owes its existence to factors specific to high-energy physics and whether the same approach could be applied in other fields are very interesting questions. (For details of SCOAP3, please refer to the SPARC Japan website.1)

High-energy physics, the field that studies elementary particles and the ultimate laws of the natural world, attracts researchers who love to argue from first principles. I am no exception, and for this article I asked myself for whom journals exist. As Kenichi Ueda noted in his lecture at a SPARC Japan seminar, journals mean different things to different people. But on reaching the obvious conclusion that ultimately it is researchers themselves—not libraries or publishers—who need journals, it strikes me as regrettable how little attention Japanese high-energy physicists themselves have paid to this question until now. Researchers, I would say, need journals to learn about other people’s work and to draw on that knowledge in their own research, then to announce their results, submit them to evaluation through peer review, and have them recognized as their own findings.

Libraries, on the other hand, have the mission of collecting and preserving human knowledge for posterity, a mission that has remained unchanged since the founding of the library of Alexandria over two millennia ago. Subscribing to journals should perhaps be understood as part of that mission. As libraries around the world cooperate in the collection and transmission of human knowledge, I would like to urge those in Japan to view maintaining OA journals through SCOAP3 as part of their task of maintaining an archive of research results (albeit in the limited area of high-energy physics), and to participate in the work of SCOAP3 as a nationwide collaborative effort.

If journals are of researchers, by researchers, and for researchers, it follows that researchers should pay for them. The subscription fee model charges them (and their institutions) as readers, while the publication fee model charges them as authors. Since the payments in the former case are made by libraries, the role played by researchers may not be obvious, but when we bear in mind that many universities pay for their libraries’ journals out of research funds that would otherwise be distributed to individual faculty members, it is clear that the source of the funds is one and the same and only the routes differ.

Needless to say, the researcher’s ideal journal is one to which he or she can freely contribute and which he or she can freely access, without charge in both cases. Further, if added-value features such as a search system or usage statistics are freely available, and if material can be freely reused, again without charge, one could not ask for more. How are we to make such an ideal a reality?

Soaring journal prices are currently leading to a breakdown of the subscription model. There are instances, not only in Japan but around the world, of universities and institutions being unable to afford the subscriptions or the online access that their researchers need; as a result, a gap is beginning to develop between rich and poor researchers and between rich and poor research institutes. Readers want articles of the highest quality, and they cannot make do with a cheap, inferior substitute, as one can in the case of most everyday purchases. It is therefore tempting to give priority to the most expensive “brand-name” journals, but the price spiral is putting these out of reach. Moreover, research fields that rely on a few brand-name journals as their source of information will surely lose their diversity and go into decline. Meanwhile, journal prices continue their inexorable rise, because the publishers can see no reason to sell high-class brand-name goods cheaply.

Turning to the viewpoint of those who write research papers, as Kenichi Ueda pointed out in his lecture, we find that the publication fee model robs many less well funded researchers and labs of the opportunity to publish their work. What they would like to see are journals with low publication fees that still maintain high quality, but the laws of commerce dictate, perhaps inevitably, that these fees will rise, because quality can command a high price. It would be a sad day for the field as a whole if lack of money forced researchers to send their articles to journals that were low cost but also low rated, thereby placing them at a disadvantage in the quest for external funding. We need to realize that funding levels reflect past performance; they are not predictors of the future. We should view it as the duty of each research field to provide its members with a place where they can publish freely.

Whichever model is adopted, if it is left to take its course a wealth gap seems inevitable. What, then, should we do? I have reached the conclusion that the research community should recognize that journals are a major part of the underpinnings of the field’s advancement and, accordingly, establish ways of bearing the costs in a larger framework, rather than leaving them to be borne by individual researchers.

PTEP, the journal about to be launched by the Physical Society of Japan in January 2013, is one example of such a structure. Organizations such as KEK and RIKEN have provided their support to boost the nation’s capacity to release worldwide the findings of Japan’s original work in physics and to promote the development of the fields of particle, nuclear, cosmic-ray, and beam physics in Japan. It will be an OA (Gold) journal published in electronic form only, dealing mainly with particle, nuclear, cosmic-ray, and beam physics. Its predecessor, Progress of Theoretical Physics (PTP), was on the subscription fee model but, in becoming OA, PTEP has shifted to the publication fee model. It will come under SCOAP3, which will pay the article processing charge (APC) for papers on high-energy physics (particle physics) for three years from 2014. For articles in other fields, a system of publication fee support by KEK and RIKEN, among others, has been put in place, and it is hoped to increase the number of universities and institutes that provide such support.

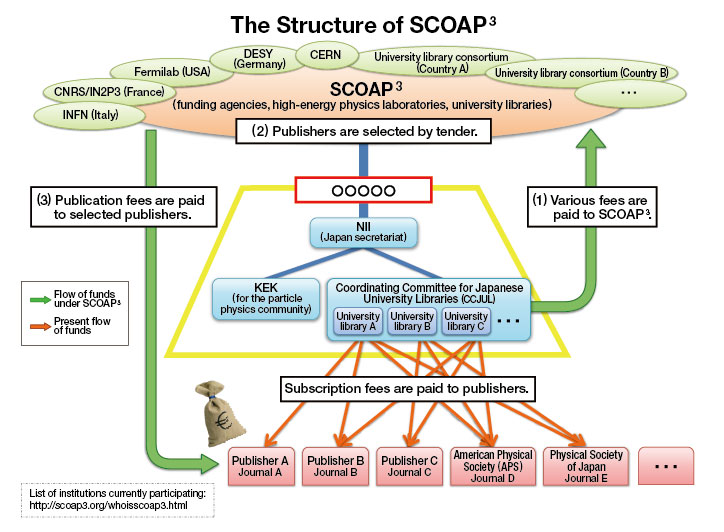

In SCOAP3, CERN has taken the lead in building a large framework to support the advancement of high-energy physics on a global scale. Publication costs have been calculated at the global level by determining the number of articles published worldwide in high-energy physics and setting a reasonable unit cost; to cover the publication costs, a consortium led by CERN will collect subscription fees in the usual way from libraries around the world. A number of underlying factors have most likely combined to make such a structure possible. Among them are the following facts: large-scale international joint experiments have become commonplace in high-energy physics, facilitating the creation of a structure for consensus-building in the researcher community; CERN has a deep understanding of OA, having for many years used and managed a preprint submission and publication system interconnected with arXiv.org; CERN and three other laboratories have built INSPIRE4 on their own, thereby providing the community with search functions and usage statistics and gaining know-how on dealing with publishers; submissions in high-energy physics are concentrated on no more than ten journals; research institutes such as CERN form the core of the research community; and the community as a whole has a shared sense that they are somehow all in this together.

There are other possibilities for large frameworks. One would be individual universities setting up structures to support article submissions by their researchers in order to advance research in the name of the institution. Many overseas universities and research laboratories have their own support systems for OA journals. It would also be very encouraging if the Japanese government were to support Japan’s OA journals under the banner of strengthening original Japanese research work, though this may be a less realistic prospect.

A larger framework is essential, in any case, if freedom of publication and access is to be guaranteed and research activity revitalized regardless of the wealth gap among researchers. Interventions can be foreseen at the national level, the university and laboratory level, or the community level, but as none of these on its own will provide a panacea, it is vital that all concerned address the issues at each of these levels.

No matter what the framework, however, the fact is that there are limits to the support that can be provided. PTEP was able to avoid problems because it is the only Japanese journal in its field. SCOAP3 narrowed to twelve the journals in which it sponsors publication, judging the candidates on price, by calling for tenders, as well as on quality. The bigger and broader the framework, the more issues arise when it comes to narrowing its scope: which journals to sponsor, which fields, which articles, and so on. I can only hope that all concerned will have good ideas to offer.

Can the SCOAP3 approach be applied to other fields? If freedom of publication and access is to be the goal, then a large framework will be needed, but it is up to each field to decide how to achieve that in keeping with its circumstances and its history, and I think that libraries should discuss this fully with researchers in every field. Support at the university level, on the other hand, seems to me a little more practicable. For example, imagine a system came into being in which all journals adopted OA and charged publication fees, and all university and research institute libraries paid those fees unconditionally for their researchers. This would mean the redirection from subscription fees to publication fees could be realized right away on a national scale.

To maintain a high level of quality, a journal publisher accepts only a limited number of articles and charges a high publication fee; thus, journals would most likely eventually separate into two classes, “brand-name” titles with a high fee and low acceptance rate, and “mass” titles where the reverse is true. Libraries would act as windows for submissions, rather than subscriptions, and negotiate discounts on publication fees, instead of journal prices, with the publishers.

However, this could be said to merely recast the problem without solving it, since a university strapped for research funds would no doubt have as much difficulty paying publication fees as it did subscriptions. As one university cannot pay another’s fees, to avoid a gap between rich and poor the need still arises for some sort of mutual assistance within the community that shares the goal of advancing the field as a whole. If the “law of the jungle” becomes the paradigm, research communities will end up consisting of a select few. In the short term, this might well result in high productivity, but in the long run the field as a whole would risk atrophy. In any field, it is surely vital to stay diverse.

SCOAP3’s use of tenders also has the important role of curbing soaring prices. The APCs of the sponsored journals are listed on the SCOAP3 website.5 Whichever model is adopted, a function that holds down price rises must be built in, separately from the support. Under the subscription fee model, I believe libraries have managed to be effective, up to a point, by forming consortia to negotiate prices. For OA journals, however, the only effective mechanism of which I am aware is to select the sponsored journals by calling for tenders, as SCOAP3 has done. But not every field will necessarily have a central institution like CERN that can take the lead in forming a consortium like SCOAP3. It is to be hoped that new ideas will be put forward from all quarters.

Lastly, a future issue for SCOAP3, in my view at least, is whether it can maintain the approach of redirecting library subscription fees. Each library’s share of publication costs, based on its 2013 subscription fees, will be maintained for three years after the system starts up in 2014, but it is unclear what would be a rational basis for determining those figures thereafter. Also, as the shares of publication costs at the national level are presently based not on each country’s total number of library subscriptions to the sponsored journals but on the total number of articles published by its researchers, some countries may have difficulty financing their share by redirection from subscriptions, while others will get a free ride. (Japan, as it happens, is one of the countries that publishes many articles but has a relatively small number of library subscriptions.) Basing cost shares on the number of articles seems to me the right approach; to make it work, during the first three years, while the shares remain fixed, we must establish the principles and the structure that will make it possible to ask research universities and other institutions with a high ability to release research findings for a bigger share than they have paid so far.

Source: Nozaki Mitsuaki (2012), 5th SPARC Japan Seminar 2012. http://www.nii.ac.jp/sparc/event/2012/pdf/20121026_6.pdf

References

|