Kazuhiro Hayashi

(National Institute of Science and Technology Policy (NISTEP);

SPARC Japan Steering Committee)

● Introduction

Changes in Reference Management and Scholarly Communications

It is already old news that we have entered an era in which electronic journals are the rule. For those involved in scholarly communications, at least in research fields where English is the main language, digitization is no longer the prime objective. The question facing us now is how researchers can best make use of digitized or digitally created information in their communications and their research work. A recent focus of attention is the debate about reference management tools and how best to utilize them in scholarly communications. In 2011 and 2012, I crossed paths several times with Victor Henning, CEO of Mendeley Ltd., whose reference management tool is currently in the spotlight, and I had the opportunity to make his acquaintance. Mendeley could be called the iTunes of scholarly papers; it has been described both as a next-generation reference management tool and as a new form of social media. In 2011, when Dr. Henning visited Japan for the first time, I organized a seminar at NISTEP under the title “The Revolution of the Reference Management Tool and Its Huge Potential Power in Scholarly Communications,”1 and a shorter version of the lecture he gave that day was subsequently published in a Japanese journal.2

These have had considerable impact and have been cited in articles including an introduction to Mendeley3 and a discussion from the viewpoint of libraries,4 and have even prompted consideration from the viewpoint of the social sciences.5

Why has Mendeley’s advent had such an impact on the world of scholarly communications, and why is Dr. Henning the man of the moment? In organizing the seminar, I enjoyed puzzling over a program that would draw him out on the origins and aims of Mendeley, as far as possible in the context of scholarly communications. As a SPARC Japan seminar that I had had a hand in planning a few days earlier had dealt with the workings of such tools and compared Mendeley to the others,6 I decided that the NISTEP event should focus primarily on Dr. Henning’s career as an entrepreneur, together with the future of scholarly communications using Mendeley. In preparing for the seminar, I also looked back at the early development of reference management tools and reconsidered the changes they have undergone from the viewpoints of the environment for information management and the methods of scholarly communications. In this article, I would like to present that overview and then, taking it as a point of departure, try to predict the future to some extent.

● Electronic journals today

As scholarly e-journals are still evolving, I would like first to take note of their current state. Their development began with digitization of the information that is the substance of scholarly communications, which until then had been handled by printing and physical distribution. Digitization began before the environment for transmission of information over the Web was fully in place, though opinion differs as to whether it originated in Elsevier’s trial called the TULIP project or in earlier initiatives such as the Online Computer Library Center (OCLC) or the digital data transmission project of the American Chemical Society. From the late 1990s to the early 2000s, as communication via the Web spread, it became easier to publish digitized information, and it also became possible to conduct peer review online. Today, several thousand journals carry on their submissions process and peer review online using a single platform, and there are a number of platforms capable of hosting several thousand journals. Each journal links to others through services such as CrossRef, or by means of bibliographic or citation databases such as Web of Science or PubMed. Further development has made it increasingly possible to link to different types of databases, for example, databases of substances, compounds, or genes, and also, most recently, databases of researchers, such as ORCID. Innovations like application programming interfaces (APIs) enable users to mash up various databases for analysis and processing, rather than simply link them, and thus to create new services or candidates for new tools to measure value. To take an example familiar to publishers and editors, CrossCheck helps detect slander and plagiarism using the electronic texts of scholarly articles that publishers supply to one another, in addition to information available on the Web. For assessing online impact, a set of tools beginning to be widely adopted is altmetrics, which quantifies the response of social networks on an article-by-article basis. Today, if publishers want to measure the response to an article by accessing nonacademic databases, they can track the reaction on Twitter and in the blogosphere instantly and thus quantify impact faster than in the days of citation counts. It is against this background of e-journals and their environs that Mendeley has become popular with researchers.

● Changes in electronic communications and storage

Electronic scholarly communications originated in academia as a subject of research, and for a while the development work necessary for journal digitization was more advanced there than in society at large. Web-based e-mail is an example of a technology originally limited to universities that later spread out into society. But, as readers are no doubt aware from everyday experience, society has lately taken the lead in electronic communications. To summarize briefly: before the Web, we exchanged information using paper, the telephone, and the fax machine; since the Web took hold, first e-mail became popular, followed by the use of Bulletin Board Systems (BBSs), then websites and portal sites, and since about 2005 new tools and media such as blogs, Peer-to-Peer (P2P) file sharing, and Skype have emerged. Information exchange via the Web accelerated in society at around that time, and in the watershed years of 2006 and 2007 social media such as social networking service (SNS) and Twitter began to appear and catch on explosively. Today society is communicating electronically in multifarious ways, and the new media gained enormous influence, even triggering political revolutions such as the Arab Spring. Among researchers, however, thus far e-mail is the only communications technology to stake out a dominant position. At some point—exactly when is hard to say—the research community and society have swapped places, and the electronic communications infrastructure has begun to evolve faster in society at large.

The Successive Versions of Reference Management and Communications Tools

| Version |

Means of

Communication |

Method

of

File

Exchange |

Databases |

Main Article

Format |

Reference

Management Tool

(Year of release)

|

| 0 |

Letter |

Postal mail |

Paper archives |

Paper |

Filing binders |

| 1 |

E-mail |

E-mail attachments |

PC

(local only)

|

PDF |

EndNote

(1988) |

| 2 |

web |

Sharing on the Web |

PC + Web |

PDF |

RefWorks

(2002) |

| 3 |

SNS |

Sharing in the cloud |

Cloud + PC |

PDF |

Mendeley

(2008) |

| 4 |

? |

Sharing of content

created in the cloud? |

Cloud only? |

Post-PDF? |

? |

Another important element of the environment that supports scholarly communications is storage. Before the Web and digitization, naturally we used information in printed form, which was physically present on our desktops and bookshelves and library stacks, and “storage” meant storage of paper. Then it became possible, first, to store information on personal computers. The external storage media in that early era of local storage included floppy disks, CDs, magneto-optical disks, and DVDs, and capacity expanded still further as hard disk drives (HDDs) came to be widely used. Around the same time, it became possible to keep data in HDDs and other storage media in relatively closed networks. The increasing speed of network circuits has also helped usher in an era when information can be stored by securing a sizable area in the cloud.

● The successive versions of reference management tools

Thus we come at last to reference management tools. All of these changes in the digital environment have had a direct bearing on how researchers exchange and circulate information. Like everybody else, researchers today are inundated by information. There is a vast amount that they need to read for their research, and they must produce as many papers as they can as documentation outcomes of their research, citing the maximum possible number of references. When they apply for funding or seek a promotion, they must fill out numerous forms and list their own articles and related literature. Paper files have continued to be used, as people are more comfortable using them and so make up reasons to continue that habit. Paper files have reached their limits, though, and so has managing information by creating folders on a personal computer. Accordingly, reference management tools are in the limelight.

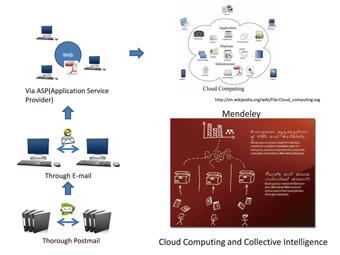

Recently, I have tried explaining the styles of reference information management by classifying them into versions 0, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0, based on the history of changes in scholarly communications discussed above. First, before the Web and digitization, we naturally stored everything in our own physical space, and the only way to exchange information was through the postal service—a physical distribution infrastructure. If this is considered the basis, or Version 0, then in 1.0 we became able to store reference files on our computers and send them by e-mail. In 2.0, we became able to place reference information in Web space and share it by communicating the URL or related data. Today we are in 3.0, where information is stored in the cloud and people can crowdsource, or collectively create, the databases they need by co-using other people’s data. At this stage, it is possible to measure the performance of scholarly articles by analyzing their information storage record and access logs.

The corresponding reference management tools would be as follows: In Version 0, we filed papers in binders and document boxes. Version 1.0 was marked by the appearance of EndNote in 1988; researchers began to store reference information locally on personal computers, mainly in support of their own writing. Version 2.0 arrived in 2002 with RefWorks; reference information could then be uploaded to the Web via an application service provider (APS) service and its location shared by e-mail or other means. Then came Version 3.0 and what is known as “born on the cloud” computing: in Mendeley, first released in 2008, reference management acquired new elements allowing researchers to jointly create a database (co-creative, collective intelligence) and jointly evaluate it (co-evaluation), rather than merely share it, so that the longer it operates, the bigger and better it becomes. Other tools of this 3.0 type include ReadCube, originally developed by two Harvard students and released by Digital Science, a sister company of the Nature Publishing Group (a division of MacMillan), and, in Japan, TogoDoc, the brainchild of Tokyo University’s Dr. Wataru Iwasaki, which could be said to be the biomedical equivalent of Mendeley. I should mention that, although I introduced EndNote and RefWorks as examples of Versions 1.0 and 2.0, they have not stood still but are rapidly approaching 3.0 iterations through continual updates, together with differentiation from other tools and ongoing improvement with an eye to the future. In any case, when reference managers take on co-creation and co-evaluation capabilities, as they have in 3.0, they are no longer simply tools for reference management but a medium of communication; at this level, reference management should be seen as a service that forms part of the ecosystem of scholarly communication.

● What the changes in reference management tools suggest about the potential of next-generation scholarly communications

This brief backward look suggests that a kind of law is at work. It may be an exaggeration to call it a law, but, simply put, reference management tools have progressively developed to meet researchers’ needs within the limits of the available communications environment. Thus, Mendeley could be seen as a product of its times, rather than an arrival out of the blue.

Then why is it receiving such a burst of attention? One reason may be its appropriation of a system established outside the academic world, as Mendeley uses the engine of Last.FM, the iTunes of FM radio programs. It can therefore offer stability, being a customized version of an information service infrastructure already up and running in society; as noted earlier, this is a reversal of the way things once worked. Another major reason is probably the fact that it was founded by researcher-entrepreneurs. Instances abound of researchers (or former researchers) creating services that they want themselves, or that their contemporaries need, such as the impact factor (Eugene Garfield), the World Wide Web (Tim Berners-Lee), and arXiv.org (Paul Ginsberg). Mendeley was reportedly created when Victor Henning and his two co-founders were struggling with reference management while working on their PhDs. When a service has its origins in a researcher’s own needs or curiosity, it tends to have a rocky road as it goes commercial, but the fact that Mendeley has succeeded in obtaining financing from the founder of Last.FM, among others, and expanding very smoothly as a business is probably another reason for its doing so well. In short, I believe it is a key point that Mendeley has secured inputs of information infrastructure, capital, and human resources, all of which were once difficult for the stakeholders in scholarly communications to come by.

What will an eventual Version 4.0 be like? Extrapolating from the pathway that led from 1.0 to 3.0, we can expect to see, first, a quantum leap in the communications environment, then the development of a tool optimized for the new environment. It will be a customization of an infrastructure already popular in society, rather than one developed from scratch for the purpose of scholarly communications. The developers will, again, be young researchers driven by some current need, and capital and human resources may come from an unlikely source. That is the kind of pathway we can foresee, extrapolating from past experience. A phenomenon that could conceivably produce a quantum leap is the growing use of the cloud. For example, the nature of reference management will change if authors no longer keep local copies of their papers but write them entirely in the cloud. A move beyond the PDF text file is also on the cards. If I had to cite one outdated aspect of Mendeley’s present system, I would name the fact that one of its main trigger events is saving a PDF. When a PDF is saved bibliographic data is automatically extracted and recorded. This feature is effective and the trigger event is very realistic for the situation today so I have no argument with it over the near term. However, the changing role of the PDF text file will bear watching in future if, as expected, tablet computers become common. If full-text files that are independent of paper begin to circulate on a truly large scale, tools may be developed for a post-PDF pathway. In addition, Dr. Henning himself states that the nature of peer review will change. There is debate over who should guarantee the quality of research results that someone wants to make public and how this should be done, or whether they should be published without a guarantee and their evaluation left to posterity. This raises the question of whether the e-journals that concern us here, or services that are an expansion of e-journals, are the ideal medium for announcing research results. The meaning of “reference” in reference management could change as a consequence of this debate and, naturally, the management tools would change also. But is that likely to happen? How long will this evolution continue? It is virtually impossible to see so far into the future.

According to Yashio Uemura of Senshu University, the revolution in information distribution brought about by Gutenberg’s mechanical press required two and a half centuries to finally permeate society and settle down.7 The revolution brought about by the Web infrastructure is a mere two decades old, and it will probably take a good many years, though not on the same order, until it in turn settles down. During that time, the communications environment of society will be in flux, and the style of information exchange among researchers may change as a result. I would be interested to know how many versions it took for print journals to settle down in the Gutenberg era, assuming that the form of information distribution went through a series of changes, hidden from us now by history, based on a perspective like the one explored here.

References

| 1. |

NISTEP Seminar. “Kenkyūsha comyunikēshon o konpon kara kaeru bunsho kanri no henkaku” [The revolution of the reference management tool and its huge potential power in scholarly communications]. NISTEP Lecture no. 286, 2011-12-08. The present article is based on the overview I presented at the beginning of this seminar, with extensive additions.

|

| 2. |

Victor Henning. “Kenkyūsha comyunikēshon o konpon kara kaeru bunsho kanri no henkaku: Mendeley CEO ga kataru gakujutsu jōhō ryūtsū no shōrai” [The revolution of the reference management tool and its huge potential power in scholarly communications: The future of scholarly communications as predicted by the CEO of Mendeley Ltd.]. Jōhō kanri [Journal of information processing and management]. vol. 55, no. 4, 2012. p. 253–261. http://dx.doi.org/10.1241/johokanri.55.253 |

| 3. |

Keita Bando. “Bunken kanri sābisu Mendeley no shōkai” [Introduction to the reference management service Mendeley]. Igaku toshokan [Journal of the Japan Medical Library Association]. vol. 59, no. 3, p. 243–249. |

| 4. |

Yutaka Hayashi. “CA1775: Daigaku toshokan no sābisu toshite no bunken kanri tsūru”[Reference management tools as a service of university libraries]. Current awareness. no. 313, 2012. http://current.ndl.go.jp/ca1775 |

| 5. |

Kazuhito Oyamada. “Sōsharu media no fukyū ga kagaku kenkyū ni motarasu henka”[How the spread of social media is changing scientific research] in Kenkyū kaihatsu senryaku rōnchi auto [Research and development strategy launches]. no. 31.

http://scienceportal.jp/reports/strategy/1201.html |

| 6. |

National Information Institute (NII). The Second SPARC Japan Seminar 2011. Workshop on “Imadoki no bunken kanri tsūru” [Contemporary reference management tools]. http://www.nii.ac.jp/sparc/en/event/2011/20111206en.html

|

| 7. |

Yashio Uemura. “Dejitaru kontentsu to insatsu media” [Digital contents and print media] (Keynote Speech for Imaging Conference Japan 2011, Imaging Society of Japan, June 6, 2011). |

|